Prior to my summer blogging hiatus, I had posted a couple of entries on some responses to Mara Hvistendahl’s recent book on the social consequences of widespread sex-selection abortions in Asia. I ended up requesting the book from my local public library, and checked it out in mid-July. I couldn’t get past the prologue; it was dreadful.

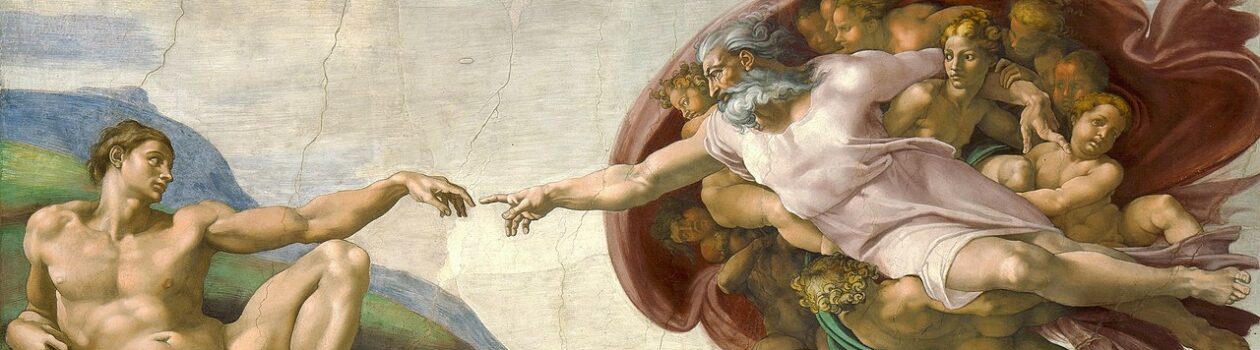

As Hvistendahl laid out her project in the prologue, it was hard not to detect something like a sadness for a great hope gone bad; a belief that abortion should have been not just a means for individual women to “gain control” of their own lives, but a vehicle for social transformation, one sure to lift the world out of the darkness of an evil past. In other words, it was supposed to be a shining example of the fundamental piety (and conceit) of progressivism: the new, technologically-empowered order of Modernity triumphing over the evil institutions of tradition. And yet, something had gone terribly wrong, somehow:

While ultrasound technology was modern, like many people at the time I thought that using it for something as crass as sex selection had to be temporary; one last instance of sexist traditions rearing their ugly head. (p. xiif)

It’s scary to consider how normal this thinking appears to many people – especially educated people.

There’s not a lot of need to explore in too much further detail the fundamental intellectual and moral error embraced by Hvistendahl: as if it were morally unacceptable to select for boys, but perfectly acceptable to select for health traits or some other eugenic purpose – or more to the point: that the practice of adults deciding which children to kill in utero can be justified on the basis of any utilitarian calculation, but only as long as the intention does not violate the sensibilities of people like Mara Hvistendahl. Abortion can’t be wrong simply because it is murderous, but it can be a thought crime, if your reasons don’t pass muster. Imagine that.

I understand that professional academics generally occupy a rather different world than that of working stiffs like me: they travel within their own peculiar orbit of fashionable dogmas that seek to explain the world according to mythologies that place professional academics themselves at the epicenter of a deterministic universe, as gatekeepers to the science of the Answers to Everything™. They function as the Priesthood of Progress – and if they also wear a white coat, then they’re like high priests, or bishops, or something. I get that. But what is a simple thinking person to make of fatuity such as this:

If females are scarce, males may kill a female’s existing offspring to maximize their chance at passing on their genes, inadvertently speeding up the species’ path toward extinction. (p. xv)

It’s hard to know where to start. Although written as a support for her theorizing on the declining prospects for peace in the world given the new gender imbalance among mankind in Asia, it is clearly standard-fare, goofball Darwinistic mythology – applicable, as must be the case, to sexual species generally. It’s tough enough to come up with a credible scenario wherein men might find a scarcity of women an inducement to kill other men’s children in order to try to ensure their own progeny, but to postulate such a clever motivation to irrational, purely instinctual creatures is beyond laughable. Of course, it’s hard enough to see how anyone can reconcile a Darwinist orthodoxy with an abortionist mindset to begin with, unless it is out of utter self-contempt. Still, this may seem somewhat irrelevant to my assessment of her book, but I offer it as an exemplar of the intellectual quality of the work as a whole.

What we’re given in this prognostication is a transparently dubious assertion about reality, being pressed down for validation into the quasi-sacred space of Darwinistic “explanations-of-everything via the progressive/evolutionary struggle for existence”, an intellectual playground where all kinds of absurd explanations for the world around us (sometimes derisively known as just-so stories) are readily embraced without much comment, and are supposedly validated by the fact that things are indeed the way they are (i.e. the just-so explanation for why things are that way must be true, or they wouldn’t be that way, right?). This is the logical fallacy known as affirming the consequent. It attempts to ride the coattails of a meaningless tautology (whatever exists is that which had been most likely to survive), but reads that tautology backwards, via a neo-pagan cosmology of primordial chaos and violence, into an origins mythology of a universal struggle for survival, which begets magical thinking in various affirmations of causeless effects, and assertions of motivated matter and acting secondary substance (i.e. species).

Sufficiently coated now with enough Darwinist dogma-dust so as to be protected from serious intellectual questioning, the idea is then walked back from the murky mists of evolutionary just-so-ism to a place where it can be supposed to be applicable to human society. Again, I understand how popular this kind of mental processing is, but I just can’t stomach it. Now, whether or not a theory of evolution, recognizable as such to a modern Neo-Darwinist, will ever offer a satisfactory biological explanation for the mysterious analogy of life on Earth is quite beside the point here. The point is that the kind of cheesy magical thinking exposed above, coupled with the ideological credulity already evident in Hvistendahl’s thinking on abortion, rendered the idea of a close reading of the entire work, in my judgment, a waste of precious time – although I would end up spending a bit more time scoping out the other sections to better grasp the work as a whole.

Browsing further, I found an interesting section exploring the effects of the woman shortage on marriage norms in Asia, where young women are now routinely imported as sexual commodities into countries with more aggressive girl-aborting practices, where they are very often taken by abusive men with no understanding (or concern) of how to treat women properly. There is also, of course, a burgeoning market in prostitution. In short, Hvistendahl reveals that abortion has facilitated the subjugation of the region’s poorer women in a cruel and demeaning system of sexual slavery. Who would have thought that imposing a barbaric institution designed to kill children for profit and convenience could give rise to such blatant disrespect for women as persons? Go figure!

Hvistendahl might be right about the ominous practical implications of the Asian gender imbalance facilitated by abortion technology – and championed by Western “do-gooders” – but she is blind to the root cause, which is not the prevailing circumstances themselves, but the underlying moral imbecility of embracing pure evil as a vehicle for achieving a desired good. Moreover, little do the Mara Hvistendahls of the world understand what’s ultimately in store for women in the West, whose status, in order to descend to such complete depravity, has to fall so much further than it did in societies in which women have not traditionally been viewed through the dignifying lens of Christianity. But the chickens will surely come home yet to roost, as men – increasingly alienated from any sense of duty, purpose, or responsibility in a consumerist, “liberated” society – continue, progressively, to see women not as wives and as partners in the perpetual generation of civilization in the family, but as more or less useful playthings.

The “freedom to choose” touted by abortion apologists is nothing but a fraudulent license to kill, and the price of murder is the loss of all decency. The bill for this idiocy is coming due.