BlogCatalog.com is organizing a campaign today, May 15th, to encourage bloggers around the world to help raise awareness of human rights issues by blogging about them. I think it’s a terrific idea, and was more than happy to sign up to join the campaign.

BlogCatalog.com is organizing a campaign today, May 15th, to encourage bloggers around the world to help raise awareness of human rights issues by blogging about them. I think it’s a terrific idea, and was more than happy to sign up to join the campaign.

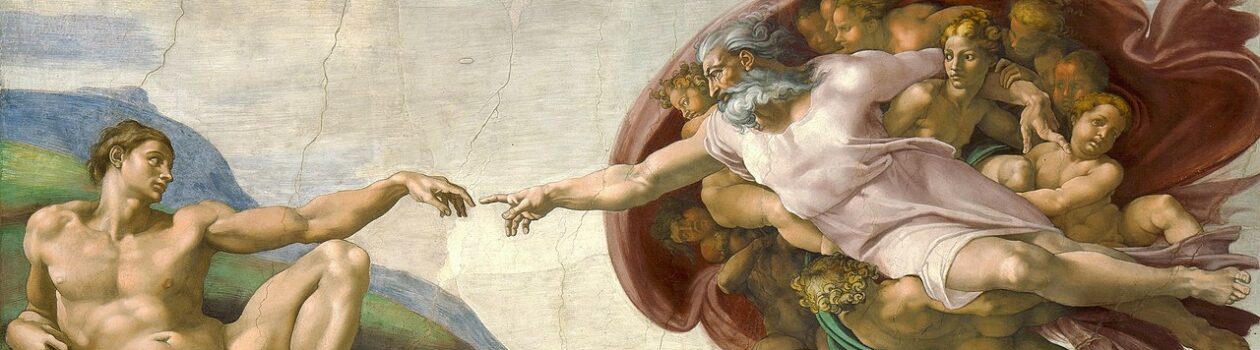

Human rights is a concept that speaks to the need for each of us to acknowledge the common humanity we share with the rest of the race, and to recognize the duties that we all inherently and inalienably have toward each other in the light of the particular dignity we each possess as human beings. Simply put, we are all brothers and sisters with a responsibility to have each other’s backs.

This is a fine sounding concept, but historically, societies have had an awful lot of difficulty living up to such a vision, even those societies that would embrace it conceptually. Someone always ends up getting the short end of the stick- or worse. We witness the injustice that society’s true prophets have always railed against – and it can take diverse forms, from economic exploitation, to limiting access to society’s goods, to slavery, to some even truly grotesque perversions.

In thinking about what kind of post I would write for this campaign, I thought it would be appropriate to look, not in some far-flung gulag halfway around the world, but in my own backyard; at my own society. I decided that I should write about the most grotesque form of injustice and offense against human rights being practiced right in my own hometown.

As I see it, there are basically two ways of subjectively understanding one’s own participation in the commission of human rights violations. The first would be to know it to be criminal. In this scenario, the culprit is entirely cognizant of the unjust nature of the violation he is inflicting upon his victim(s). He knows that what he is doing is wrong, but he does it anyway, because he has a disordered desire of some sort or another that trumps the weak voice of conscience. This may be, and in all likelihood is, a recurring pattern, but the point is that the violator has a bad conscience: true criminality involves a bad conscience, a guilty conscience, the knowledge of wrongdoing (even if the criminal is indifferent about it).

The other understanding is one that I struggle to come up with a good name for. Our criminal justice system calls it insanity – which may be accurate, but if it is, then I fear the world might be full of mostly insane people. It is the stance that calls injustice by the name of righteousness. It’s the approach that permits people to do terrible things to other human beings with a perfectly clear conscience, or at least with a repressed conscience. It involves a denial of the unjust nature of the offense, which is almost always – and perhaps absolutely always – facilitated by dehumanizing the victims. The violator sees the victim as some lesser kind of creature, as something sub-human. This conscience-evading self-delusion is essentially voluntary insanity.

Voluntary insanity can only thrive in a culture of complicity, because most people cannot hang onto insanity for long in the face of reality. Without a network of co-denial supporting a mutual self-delusion, most people are forced into either a (self-acknowledged) criminal choice for evil, or acceptance of the moral good – however reluctantly accepted. The conscience eventually confronts the will, and either it fails or succeeds to compel a moral response. Either way, there is basically full acknowledgement of responsibility on the part of the individual as a moral agent. People just aren’t usually that stupid, except as part of a mob.

Without meaning to downplay the brutality of criminality, it seems to me that the great violations of human rights are generally of the second order – they are carried out in a culture (or sub-culture) of insanity – if that’s the right word, and I’m not sure it is. There is a dehumanizing of the subjected class, who are then seen as means to the ends of the perpetrators. We end up with second-class citizens, with slave classes, with social groups selected for extermination, with classes of human beings whose very humanity is denied. And at the very, very bottom of human degradation, you end up with abortion. If "Human Rights" means anything at all, it has to begin with the right to be human.

There are many reasons abortion is the greatest social evil and violation of human rights in our day, and even a nominally educated hack like me could go on and on in explicating them, but I just want to make what I think is the very obvious point that abortion is such a great human rights crisis in our age precisely because it is so often not recognized as a human rights violation at all.

Now, that fact usually strikes pro-lifers as entirely bizarre. But that is because pro-lifers recognize that children – human beings – are intentionally killed when abortions are performed. If a pro-lifer were to be materially complicit in an abortion, it would be a criminal act (not, of course, according to current criminal law in the US, which happens to be insane, but according to the subjective distinctions I made above between criminality vs. insanity).

But like any great violation of human rights, the abortion machine is driven primarily by insanity, not by a rational criminality. It is utterly dependent for its perpetuation upon widespread complicity in the self-delusional denial of the simple truth that mothers really do go into abortion clinics to have their children killed (and of course that, in most cases, fathers are either materially complicit, or couldn’t care less – and in other cases are coercively responsible for the killing).

They may come to their senses later – many do, in great grief – but the vast majority of people involved in abortions – either directly or through political support – are engaged in the age-old practice of dehumanizing their victims in order to avoid confronting the reality of the evil they are committing. They are insane, if that’s the right word. Despite the rather obvious reality that each one of them was at one time a fetus, they deny with all their might that a fetus is in the same way one of them, one of us; that a human fetus is a human being.

I’m sure there’s a better word for this than insanity, and I wish I could put my finger on it. Hannah Arendt famously called it banality, but she, whatever her intentions, ended up exploring evil more at its roots – exposing how ordinary people can make horrific moral choices without batting an eyelash – whereas I’m simply trying to show how such a mechanism works in our current historical and social context. Nonetheless, Eichmann in Jerusalem just might be the best background reading available for understanding the moral underpinnings of the modern abortion debacle. I should probably mention that Arendt would likely protest my use of the word insanity in this context. I understand that; it is voluntary,I maintain, though that may not convince her of the word’s usefulness here.

I think this insanity factor is not often grasped by pro-lifers. Hence, they tend to project criminal intent (in my usage of the term) where it doesn’t really exist. They find it unfathomable that people involved in abortion don’t know perfectly well what they are doing. That is understandable, and at a certain level they are right (I do not propose that what I call voluntary insanity mitigates moral culpability), but I think they fail to perceive the power of human self-deception. I recall an adage that goes something like: Never attribute to malice what can be adequately explained by incompetence. Here’s a case in point I came across very recently.

Out at UCLA, there is a quarterly called The Advocate published by a small group of student pro-life activists that has put considerable effort into exposing the ugly face of the abortion industry. In particular, they have collected some very damaging information on Planned Parenthood locations in various parts of the country.

They are alleging racism on the part of Planned Parenthood, based on undercover operations that repeatedly demonstrated that the organization was more than willing to take donations from individuals who were expressly requesting their contributions be used to kill black babies, because, they complained, there are too many black babies in the world. There are transcripts and actual audio tapes of phone calls available as links from the site – but they are very creepy; not for the faint of heart.

As much as I admire the spunk of these young defenders of the defenseless, I think they are overstating the case against Planned Parenthood – damning audio tapes notwithstanding. What these kids are not grasping is the insanity factor. Those folks at PP are not accepting donations because they are specifically targeted to kill black children (that would be criminal), they just couldn’t care less, because they don’t acknowledge what is going on in their clinics (that is insanity). These workers might be made temporarily uncomfortable by the wacky telephone caller, but they really just want to collect more money to do what they consider their good work, and it doesn’t dawn on them to honestly consider the morality of how they are going about accomplishing the "social improvements" that give their professional lives meaning. Freedom is a powerful elixir, even when it’s sham facade for violence – just ask the French, who remain the standard bearers of the need to discriminate between liberty and lunacy. The bottom line is that these workers have too much at stake in keeping the moral blinders on, and focusing on the dreadful "benefits." Voluntary insanity.

This, then, is the true face of human rights violators. For every sadistic monster who fills our imaginations with righteous indignation, there is a platoon of Hannah Arendt’s Eichmanns: unremarkable folk living respectable work-a-day lives while wallowing in moral infantilism, oblivious of the evil they perpetrate in the name of social convention- a study in banality and cluelessness. Evil is most insidious when it dons the mantle of righteousness.

BlogCatalog.com is

BlogCatalog.com is